The “sharing economy” has attracted a great deal of attention in recent months. Platforms such as Airbnb and Uber are experiencing explosive growth, which, in turn, has led to regulatory and political battles. Boosters claim the new technologies will yield utopian outcomes—empowerment of ordinary people, efficiency, and even lower carbon footprints. Critics denounce them for being about economic self-interest rather than sharing, and for being predatory and exploitative.

Not surprisingly, the reality is more complex. This essay, based on more than three years of study of both non-profit and for-profit initiatives in the “sharing economy,” discusses what’s new and not so new about the sector and how the claims of proponents and critics stack up. While the for-profit companies may be “acting badly,” these new technologies of peer-to-peer economic activity are potentially powerful tools for building a social movement centered on genuine practices of sharing and cooperation in the production and consumption of goods and services. But achieving that potential will require democratizing the ownership and governance of the platforms.

Introduction

Earlier this year, hundreds of people gathered in a downtown San Francisco venue to celebrate—and debate—the “sharing economy.” The term covers a sprawling range of digital platforms and offline activities, from financially successful companies like Airbnb, a peer-to-peer lodging service, to smaller initiatives such as repair collectives and tool libraries. Many organizations have been eager to position themselves under the “big tent” of the sharing economy because of the positive symbolic meaning of sharing, the magnetism of innovative digital technologies, and the rapidly growing volume of sharing activity.

While boosterism has been the rule in this sector, a strong contingent at the conference questioned whether the popular claim that the sharing economy is fairer, lower-carbon, and more transparent, participatory, and socially-connected is anything more than rhetoric for the large, monied players. Janelle Orsi, an activist lawyer, opened with a provocative challenge: “How are we going to harness the sharing economy to spread the wealth?” The Airbnbs of the world and their venture capitalist backers are siphoning off too much value, she and others argued. Discussions of labor exploitation, race to the bottom dynamics, perverse eco-impacts, unequal access for low-income and minority communities, and the status of regulation and taxation engaged attendees throughout the next two days.

Over the last year, these and related debates have been raging within and outside the sharing community. Will the sector evolve in line with its stated progressive, green, and utopian goals, or will it devolve into business as usual? This moment is reminiscent of the early days of the Internet, when many believed that digital connection would become a force for empowerment. The tendency of platforms to scale and dominate (think Google, Facebook, and Amazon) offers a cautionary tale. So, too, does the history of Zipcar. Once the face of the sharing economy, it is now a sub-brand of Avis. Will other sharing platforms follow similar trajectories as they grow? Or will the sharing economy be the disruptive, world-changing innovation its proponents expect? And if it is, will it change the world for the better? It is too early for definitive answers to these questions, but important to ask them.[1. Over the past three years, I have been conducting qualitative research on the sharing economy funded by the MacArthur Foundation ). My research team has conducted seven cases: three non-profits (a time bank, a food swap, and maker-space), three for-profits (Airbnb, RelayRides, and Task Rabbit), and one hybrid (open-access education). We have done more than 150 interviews and more than 500 hours of participant observation.]

While many of the most visible platforms in the sharing economy began in the United States, sharing has become a global phenomenon, both because of the expansion of platforms to other countries, and because the idea of sharing has caught on around the world. Platforms are proliferating throughout Europe, where cities are becoming centers of “sharing” practices. Paris, for example, has become the annual home of the “OuiShare” fest. The Arab world has a raft of new sharing innovations, Colombia has become a sharing hub in Latin America, and Seoul is a center of sharing. Last year, the government of Ecuador launched Buen Conocer, an initiative to radically reimagine the nation according to principles of sharing—open networks, open production, and an economy of the commons.

While the politics of these sharing efforts differ across the globe, what is common is the desire among participants to create fairer, more sustainable, and more socially connected societies.

I became interested in the sharing economy in 2008 while I was writing a book about a transition to a small-scale, ecologically sustainable economy.[2. Juliet B. Schor, True Wealth: How and Why Millions of Americans Are Creating a Time-rich, Ecologically-light, Small-scale, High-satisfaction Economy (New York: The Penguin Press 2011).] At that time, I predicted a decline in full-time employment, as well as the need to reduce working hours as a method of controlling carbon emissions. I proposed a new household model in which people would have diverse sources of income, and would access goods and services through varied low-cost channels. With enough of a safety net and sufficient public goods, such a world could yield greater freedom, autonomy, and quality of life. If it were able to provide decent earnings and reasonably low prices, the sharing economy could be an important component of that new model. Today, however, with the corporatization of a number of the leading players, the role of the sharing economy in a just and sustainable transition is an open question.

It is timely to step back and take stock of what has happened and how the arguments both for and against the sharing economy stack up. Because my research has focused on the United States, this essay will do so as well, returning to the global dimensions of sharing in the conclusion. I begin with a brief review of what the sharing economy is, where it came from, and why people are participating in it. I will then consider the sharing economy’s impacts on ecological well-being and social connection. I conclude with the question of whether these new technologies and practices can lead to new forms of organizing that may be part of a citizens movement for a fairer and more sustainable economy.

What is The Sharing Economy?

Coming up with a solid definition of the sharing economy that reflects common usage is nearly impossible. There is great diversity among activities as well as baffling boundaries drawn by participants. TaskRabbit, an “errands” site, is often included, but Mechanical Turk (Amazon’s online labor market) is not. Airbnb is practically synonymous with the sharing economy, but traditional bed and breakfasts are left out. Lyft, a ride service company, claims to be in, but Uber, another ride service company, does not. Shouldn’t public libraries and parks count? When I posed these questions to a few sharing innovators, they were pragmatic, rather than analytical: self-definition by the platforms and the press defines who is in and who is out.

Sharing economy activities fall into four broad categories: recirculation of goods, increased utilization of durable assets, exchange of services, and sharing of productive assets.

The origins of the first date to 1995 with the founding of eBay and Craigslist, two marketplaces for recirculation of goods that are now firmly part of the mainstream consumer experience. These sites were propelled by nearly two decades of heavy acquisition of cheap imports that led to a proliferation of unwanted items.[3.Ibid] In addition, sophisticated software reduced the traditionally high transaction costs of secondary markets, and at eBay, reputational information on sellers was crowdsourced from buyers, thereby reducing the risks of transacting with strangers. By 2010, many similar sites had launched, including ThredUp and Threadflip for apparel, free exchange sites like Freecycle and Yerdle, and barter sites such as Swapstyle.com. Online exchange now includes “thick,” or dense, markets in apparel, books, and toys, as well as thinner markets for sporting equipment, furniture, and home goods.

The second type of platform facilitates using durable goods and other assets more intensively. In wealthy nations, households purchase products or hold property that is not used to capacity (e.g., spare rooms and lawn mowers). Here, the innovator was Zipcar, a company that placed vehicles in convenient urban locations and offered hourly rentals.

After the 2009 recession, renting assets became more economically attractive, and similar initiatives proliferated. In transportation, these include car rental sites (Relay Rides), ride sharing (Zimride), ride services (Uber, UberX, Lyft), and bicycle sharing (Boston’s Hubway or Chicago’s Divvy Bikes). In the lodging sector, the innovator was Couchsurfing, which began pairing travelers with people who offered rooms or couches without payment back in 1999. Couchsurfing led to Airbnb, which has reported more than 10 million stays.[4. Ryan Lawler, “Airbnb Tops 10 Million Guest Stays Since Launch, Now Has 550,000 Properties Listed Worldwide,” December 19, 2013,

There has also been a revival of non-monetized initiatives such as tool libraries, which arose decades ago in in low-income communities. These efforts are typically neighborhood-based in order to enhance trust and minimize transportation costs for bulky items. New digital platforms include the sharing of durable goods as a component of neighborhood building (e.g., Share Some Sugar, Neighborgoods). These innovations can provide people with low-cost access to goods and space, and some offer opportunities to earn money, often to supplement regular income streams.

The third practice is service exchange. Its origins lie in time banking, which, in the United States, began in the 1980s to provide opportunities for the unemployed.[5. Edgar Cahn and Jonathan Rowe, Time Dollars (Emmaus, PA: Rodale Press, 1992).] Time banks are community-based, non-profit multilateral barter sites in which services are traded on the basis of time spent, according to the principle that every member’s time is valued equally. In contrast to other platforms, time banks have not grown rapidly, in part because of the demanding nature of maintaining an equal trading ratio.[6. Emilie Dubois, Juliet Schor, and Lindsey Carfagna,“New Cultures of Connection in a Boston Time Bank,” in Practicing Plenitude, eds. Juliet B. Schor and Craig J. Thompson (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014).] There are also a number of monetized service exchanges, such as Task Rabbit and Zaarly, which pair users who need tasks done with people who do them, although these have encountered difficulties expanding as well.

The fourth category consists of efforts focused on sharing assets or space in order to enable production, rather than consumption. Cooperatives are the historic form these efforts have taken. They have been operating in the US since the nineteenth century, although there has been a recent uptick in new ones. Related initiatives include hackerspaces, which grew out of informal computer hacking sessions; makerspaces, which provide shared tools; and co-working spaces, or communal offices. Other production sites include educational platforms such as Skillshare.com and Peer-to-Peer University that aim to supplant traditional educational institutions by democratizing access to skills and knowledge and promoting peer instruction.[7. It is worth noting the historical and global connections between the sharing platforms and other types of P2P activity. The collaborative software movement, which harnesses the unpaid work of software engineers to write code and solve problems collectively, paved the way for file-sharing, video posting, and crowdsourcing information, as seen in Wikipedia or citizen science. The global “commons” movement is encouraging peer production and the information commons, as well as the protection of ecological commons.]

In what follows, I will use a number of terms, including providers, consumers, participants, and users. Consumers are those who are buying services, while providers, or suppliers, are offering them. Participants can be on either side of a transaction. Users is also often employed this way. For example, Airbnb calls hosts and guests users, but in other platforms, e.g., Lyft or Uber, users would be riders, rather than drivers. On the other hand, we have found in our research that quite a few people who are providers on a site also use it as consumers, so the distinction is often more useful for transactions than persons.

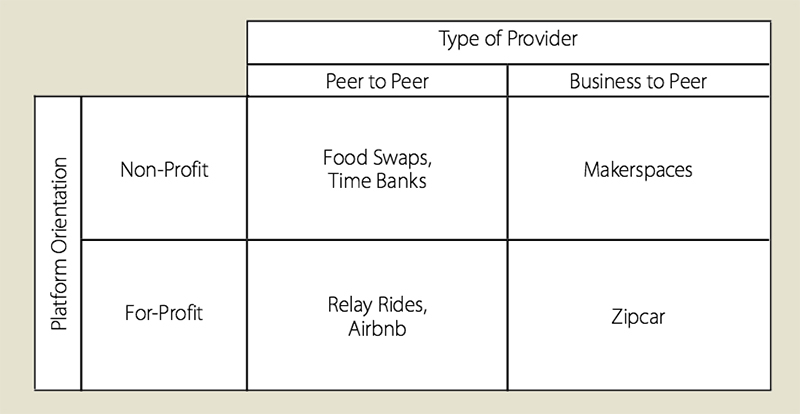

The operation and the long-term impacts of these platforms are shaped by both their market orientation (for-profit vs. non-profit) and market structure (peer-to-peer vs. business-to-peer). These dimensions shape the platforms’ business models, logics of exchange, and potential for disrupting conventional businesses. Examples of each type are shown in Figure 1.

While all sharing economy platforms effectively create “markets in sharing” by facilitating exchanges, the imperative for a platform to generate a profit influences how sharing takes place and how much revenue devolves to management and owners. For-profit platforms push for revenue and asset maximization. The most successful platforms—Airbnb and Uber, valued at $10 and $18 billion respectively— have strong backing from venture capitalists and are highly integrated into existing economic interests.[8. Andrew Ross Sorkin, “Why Uber Might Well be Worth $18 Billion,” New York Times, June 9, 2014, http:// dealbook.nytimes.com/2014/06/09/how-uber-pulls-in-billions-all-via-iphone/; Evelyn Rusli, Douglas MacMillan, and Mike Spector, “Airbnb Is in Advanced Talks to Raise Funds at a $10 Billion Valuation,” Wall Street Journal, March 21, 2014, The introduction of venture capitalists into the space has changed the dynamics of these initiatives, particularly by promoting more rapid expansion.

While some of the platforms present a gentle face to the world, they can also be ruthless. Uber, which is backed by Google and Goldman Sachs, has been engaging in anti-competitive behavior, such as recruiting its competitors’ drivers. While its representatives articulate a neoliberal rhetoric about the virtue of “free markets,” the company is apparently hedging its bets on what “free” markets will deliver for it by hiring Obama campaign manager David Plouffe to bring some old-fashioned political capital to its defense.

By contrast, many of the initiatives in the sharing space, such as tool libraries, seed banks, time banks, and food swaps, are non-profits. They do not seek growth or revenue maximization, but instead aim to serve needs, usually at a community scale.

While the for-profit vs. non-profit divide is the most important one, the divide between P2P (peer-to-peer) and B2P (business-to-peer) platforms is also significant. P2P entities earn money by commissions on exchanges, so revenue growth depends on increasing the number of trades. In contrast, B2P platforms often seek to maximize revenue per transaction, as traditional businesses often do. Consider the differences between Zipcar (B2P) and RelayRides (P2P). On RelayRides, owners earn income from renting their own vehicles, choosing trades based on their needs, and setting rates and availability. Zipcar functions like an ordinary short-term car rental company. With a P2P structure, as long as there is competition, the “peers” (both providers and consumers) should be able to capture a higher fraction of value. Of course, when there is little competition, the platform can extract rents, or excess profits, regardless.

Sharing platforms, particularly non-profits that are operating to provide a public benefit, can also function as “public goods.” A tool library is like a public library in many ways, although it is not organized by a government, not typically supported by public funds, and not necessarily governed by a democratic process. Many public goods have a G2P structure (government-to-peer), rather than P2P. But P2P structures can be, and frequently are, democratically organized.[9. For more on sharing and public goods, see Julian Ageyman, Duncan McLaren, and Adrianne Schaefer-Borrego, “Sharing Cities,” Briefing for the Friends of the Earth Big Ideas Project, September 2013,

Debating The Sharing Economy Part 2

Debating The Sharing Economy Part 3

Article first published at website Great Transition Initiative

Endnotes

Juliet Schor is Professor of Sociology at Boston. She is also a member of the MacArthur Foundation Connected Learning Research Network. Schor’s research focuses on issues of time use, consumption and environmental sustainability. A graduate of Wesleyan University, Schor received her Ph.D. in economics at the University of Massachusetts. Before joining Boston College, she taught at Harvard University for 17 years, in the Department of Economics and the Committee on Degrees in Women’s Studies. In 2014 Schor received the American Sociological Association’s award for Public Understanding of Sociology. She also served as the Matina S. Horner Distinguished Visiting Professor at the Radcliffe Institute at Harvard University.

Schor is a former Guggenheim Fellow and recipient of the 2011 Herman Daly Award from the US Society for Ecological Economics. She is a former Trustee of Wesleyan University, an occasional faculty member at Schumacher College, and a former fellow of the Brookings Institution.

She is a co-founder of the Center for a New American Dream (newdream.org), a national sustainability organization where she served on the board for more than 15 years. She is also on the board of the Better Future Project, one of the country’s most successful climate activism organizations. She is a co-founder of the South End Press and the Center for Popular Economics.

Schor has lectured widely throughout the United States, Europe and Japan to a variety of civic, business, labor and academic groups. She appears frequently on national and international media, and profiles on her and her work have appeared in scores of magazines and newspapers, including The New York Times, Wall Street Journal, Newsweek, and People magazine. She has appeared on 60 Minutes, the Today Show, Good Morning America, The Early Show on CBS, numerous stories on network news, as well as many other television and radio news programs.