Measuring people’s wellbeing is critical for a government. Like that, police-makers and other institutions can get to know first-hand where the inequality gaps lie within the people’s overall welfare. However, standards followed until now have relied upon personal and subjective data, two variables that clearly interfere with the final results.

Self-reported life satisfaction or even happiness have been used as standard deviation with great weight in recent researches. Although, academics have always suspected that these two variable might carry along inaccurately given data, as people tend to say how they feel depending on the situation they are going through.

However, the debate whether if these measure standards are the most appropriate or not have had a limited effect and statistics have been released without proper discussion, even though if those were inaccurately or a partial representation of the whole citizenship feelings.

For instance, these measures should be robust to biases and a good reflection of the underlying phenomenon they are trying to measure, for example economic growth or contributions to climate change, if they are to help police-makers making the right decision for a given issue.

A new research carried out by the New Economic Foundation explores “the strengths and weaknesses of different measures of wellbeing inequality and to make a recommendation of a measure which could be reported by the ONS alongside mean wellbeing.”

And so and after meticulously taken every methodology previously conducted, they concluded that a good indicator of wellbeing inequality is reflective of public and political priorities; following a series of must-have characteristics such being robust to methodological biases; easy to construct and analyse; can be communicated easily; is sensitive enough to reflect policy change; associated with other outcomes of interest; and adds additional information over and above the widely used measure of average wellbeing.

For that this new measure should have all hypothesis covered and therefore it should be easy to compute, easy to communicate, subject to a predictive power, and being aware of the variation over time and low correlation with the mean well-being.

Once the methodology was picked, they went to answer the big question: what to measure?

In the report, they ended up getting to the conclusion that applicants had various apprehensions for caring about inequality for a wellbeing status, these apprehensions indeed can be at the same time divided into three ethical propositions.

- The first, stated as Dispersion Aversion, is a belief that policy should be focussed on those with very low wellbeing, to establish a threshold under which people should not fall.

- The second, what they called Weighted universalism, is the desire to reduce the gap between those with very high wellbeing and very low wellbeing, in the belief that such a gap may create social disruption or damaging social comparisons.

- The third, Suffering aversion, goes into improving everyone’s wellbeing, but focusing on the concern to be weighted to the worst off, not to the highest good. This final proposition was found the most dominant both in revealed preferences and through explicit expressions of peoples’ views.

These ethical positions are different but not mutually exclusive. For example, “it is

consistent to have both an aversion to dispersion and a desire to ameliorate suffering.

The positions are intentionally stylised and in practice, most people would hold at least

two; however, the question of what we should measure boils down to the relative

importance we give to these different ethical propositions,” they pointed out the researchers.

Measuring wellbeing inequality: Results

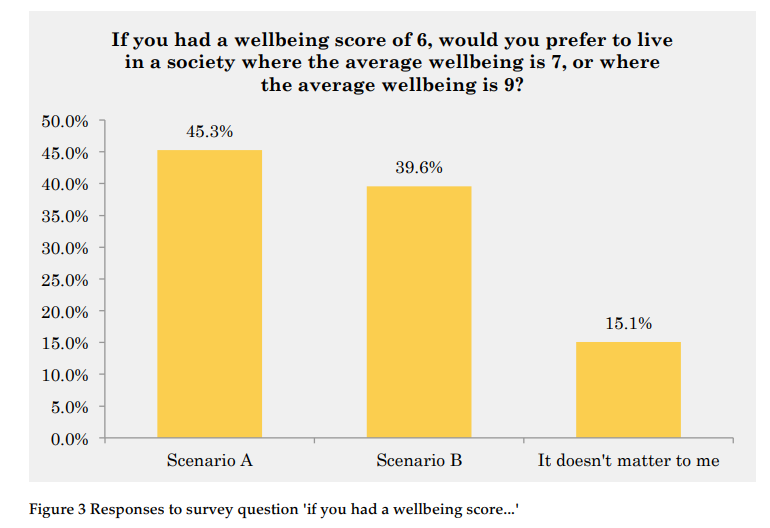

Although all three ethical propositions were held to some extent by some participants, the research suggested that weighted universalism was more widely shared than the other positions, and it makes sense theoretically. This submits that an inclusive wellbeing indicator should first and foremost reflect the wellbeing of the worst off, with diminishing weight given to those higher up the ladder.

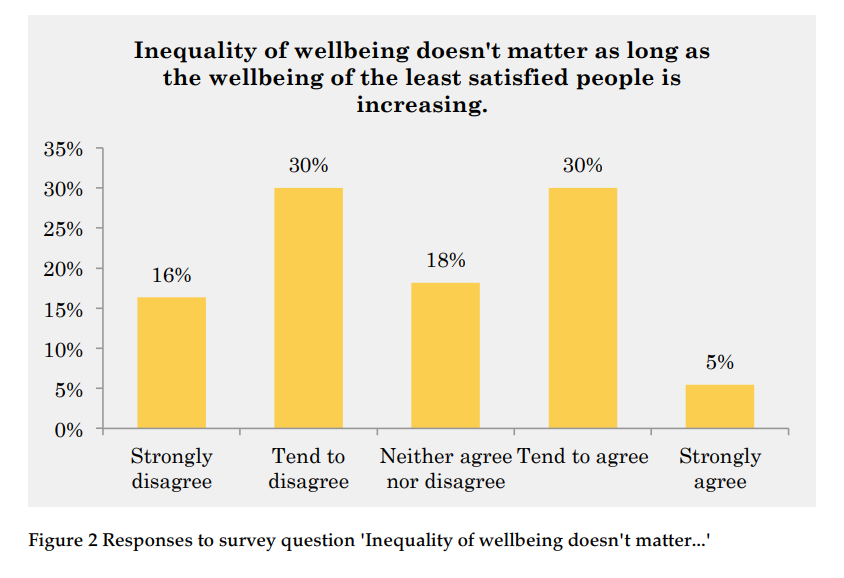

However, they added that “it is interesting to note the strength of dispersion aversion amongst some participants. The interviews and own research have identified legitimate reasons to be concerned about wide gaps in wellbeing, including values-based reasons about fairness and social justice, as well as instrumental concerns such as social unrest.”

In contrast to the other two proposals, aversion to dispersion suffers from a number of weaknesses as a strict ethical proposition, although still a well accurate variable within a full wellbeing measuring.

Through this methodology, researchers at the New Economics Foundation tried to make up an all-inclusive wellbeing inequality measure. Applicants’ answers must be taken in consideration depending on three ethical propositions, all related and accurately driven to get the best results out of a complex and non-scientific measuring.

Hernaldo Turrillo is a writer and author specialised in innovation, AI, DLT, SMEs, trading, investing and new trends in technology and business. He has been working for ztudium group since 2017. He is the editor of openbusinesscouncil.org, tradersdna.com, hedgethink.com, and writes regularly for intelligenthq.com, socialmediacouncil.eu. Hernaldo was born in Spain and finally settled in London, United Kingdom, after a few years of personal growth. Hernaldo finished his Journalism bachelor degree in the University of Seville, Spain, and began working as reporter in the newspaper, Europa Sur, writing about Politics and Society. He also worked as community manager and marketing advisor in Los Barrios, Spain. Innovation, technology, politics and economy are his main interests, with special focus on new trends and ethical projects. He enjoys finding himself getting lost in words, explaining what he understands from the world and helping others. Besides a journalist, he is also a thinker and proactive in digital transformation strategies. Knowledge and ideas have no limits.