Science, technology, engineering, and math have been historically male-dominated fields, but trailblazers like Karen Uhlenbeck are proving that they don’t have to be. Uhlenbeck is shattering stereotypes simply by succeeding in her field and showing girls and women everywhere that anything is possible.

We all recognise this names: Pythagoras, Euclid, Guillaume L’Hôpital, Johann Bernoulli, John Nash. We grew up used to listen to these people as important names, of people who made History, through their outstanding mathematical contributions. Unfortunately, nearly all the names we have grown to hear, are names of men. But in reality, many women gave incredible contributions to the world even though the history manuals don’t narrate their stories or even give us their names.

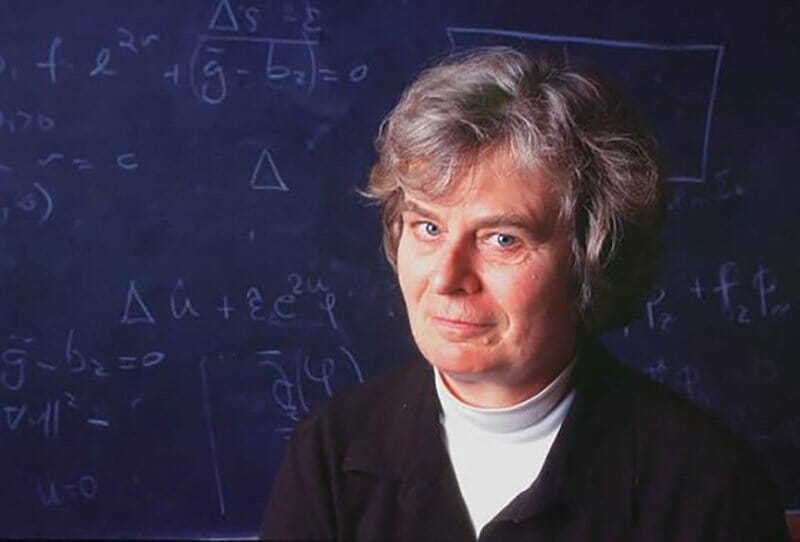

Are things changing now? This week, an important thing happened. Karen Uhlenbeck, a mathematician, and University of Texas professor became the first woman to win the Abel Prize, considered the “Nobel Prize of Math,”on Tuesday

Uhlenbeck’s decades of work have touched on several disciplines, including geometry, quantum theory, and physics. The prize, according to the prize’s website. though mainly recognizes her for her “pioneering achievements in geometric partial differential equations, gauge theory and integrable systems, and for the fundamental impact of her work on analysis, geometry and mathematical physics,”

The Abel Prize, first awarded in 2003, is bestowed by the King of Norway and comes with a 6 million Norwegian kroner (approximately $700,000) cash prize.

Uhlenbeck is already a consecrated mathematician, having previously won the National Medal of Science in 2000 and receiving a MacArthur Fellowship — also known as a “genius grant” — in 1983.

“Uhlenbeck’s research has led to revolutionary advances at the intersection of mathematics and physics,” Paul Goldbart, dean of the University of Texas’ College of Natural Sciences, said in a statement.

“Her pioneering insights have applications across a range of fascinating subjects, from string theory, which may help explain the nature of reality, to the geometry of space-time,” he added.

When interviewed for the New York Times Uhlenbeck mentioned how she has been acutely aware of the unique opportunity she was a role model for the next generation of women in academia. Growing up, she said her own role model was famed chef and television personality, Julia Child.

“I certainly very much felt I was a woman throughout my career. That is, I never felt like one of the guys,” she said.

Still she considers herself lucky, telling the Times, “I was in the forefront of a generation of women who actually could get real jobs in academia.”

Almost as important as her contributions to her field, are Karen Uhlenbeck’s contributions to the next generation of women. Pioneers like Uhlenbeck help show women and girls around the world that science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) fields, which have traditionally been male-dominated, do not need to remain so.

The importance of this prize lies not only about helping to advance the field of mathematics, but shattering gender stereotypes. True gender balance, though, will only happen, when we will see men stepping into careers considered to be traditionally, more female oriented, like education and social action. And then, the next step for even truer gender parity, will only occur, when we will see men staying at home with their small kids equally as long as women, and gaining prizes for that maybe!

Founder Dinis Guarda

IntelligentHQ Your New Business Network.

IntelligentHQ is a Business network and an expert source for finance, capital markets and intelligence for thousands of global business professionals, startups, and companies.

We exist at the point of intersection between technology, social media, finance and innovation.

IntelligentHQ leverages innovation and scale of social digital technology, analytics, news, and distribution to create an unparalleled, full digital medium and social business networks spectrum.

IntelligentHQ is working hard, to become a trusted, and indispensable source of business news and analytics, within financial services and its associated supply chains and ecosystems